Rosh Hashanah , the Jewish New Year, starts at sundown on September 20, 2017. It’s known for apples dipped in honey, record synagogue attendance and as the kickoff to the Days of Awe, which culminate in Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. We’re guessing that even the most experienced holiday observer, however, won’t know all of these facts about the holiday:

1. It’s traditional to eat a “new fruit,” or fruit you haven’t eaten for a long time, on the second night of Rosh Hashanah.

This tasty custom is often observed by eating a pomegranate, a fruit rich in symbolism (and nutrients). It developed as a technical solution to a legal difficulty surrounding the recitation of the Shehechiyanu blessing on the second day of the holiday. Use it as an excuse to scout out the “exotic fruit” section of your grocery store’s produce department.

2. And speaking of fruit, apples and honey (and pomegranates) aren’t the only symbolic foods traditionally enjoyed on Rosh Hashanah.

Other foods traditionally eaten to symbolize wishes for prosperity and health in the new year include dates, string beans, beets, pumpkins, leeks — and even fish heads. Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews often hold Rosh Hashanah seders in which a blessing is said for each food, and they are eaten in a set order. If you want to try this but are a vegetarian or just grossed out by fish heads, consider using gummy fish or fish-shaped crackers instead

3. Rosh Hashanah liturgy has inspired at least two rock songs.

This lively gathering, which dates back to the early 19th century (and has nothing to do with the Israeli kibbutz movement), takes place in Uman, the town where Nachman of Breslov, founder of the Breslover sect and great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, was buried. Breslov believed Rosh Hashanah was the most important holiday, hence the timing of the pilgrimage.

4. Tens of thousands of Hasidic Jews make a pilgrimage to Ukraine for an annual Rosh Hashanah gathering known as a “kibbutz.”

This lively gathering, which dates back to the early 19th century (and has nothing to do with the Israeli kibbutz movement), takes place in Uman, the town where Nachman of Breslov, founder of the Breslover sect and great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, was buried. Breslov believed Rosh Hashanah was the most important holiday, hence the timing of the pilgrimage.

5. It is traditional to fast on the day after Rosh Hashanah.

The Fast of Gedaliah is not a cleanse for those who overindulged at holiday meals, but a day set aside to commemorate the assassination of Gedaliah, the Babylonian-appointed official charged with administering the Jewish population remaining in Judea following the destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C.E. Unlike Yom Kippur, which comes just a few days later, this fast lasts only from sunrise to sundown.

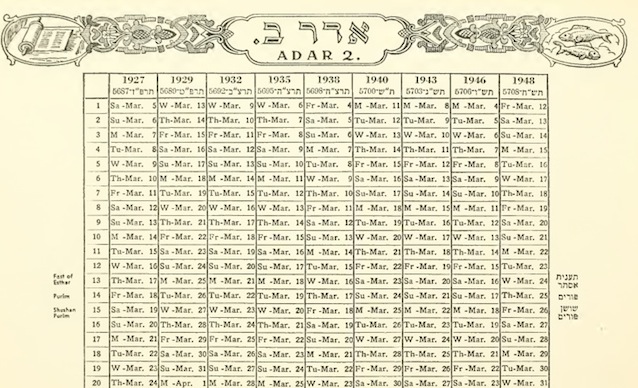

6. If Rosh Hashanah felt ‘late’ in 2016, that’s because it was.

The latest date that Rosh Hashanah can fall on the Gregorian calendar is October 5 (as happened in 1967 and will happen again in 2043). It wasn’t quite that late in 2016, but was on the later end because we were in a Jewish leap year — which is more complicated than the Gregorian leap year of adding a day to February every four years. To coordinate the traditional lunar year with the solar year and ensure that the season in which a holiday falls remains consistent, Judaism worked out a system of 19-year cycles, during which there are seven leap years. Instead of adding a day, the Jewish calendar adds a full month — a second Adar — to the year.

7. American Jews used to exchange telegrams for Rosh Hashanah. A LOT of them.

In 1927, the Western Union Telegraph Company reported that Jewish people sent telegrams of congratulations and well-wishing much more frequently than members of any other group. In particular, they exchanged thousands of messages for Rosh Hashanah. “So great has the volume of this traffic become that the Western Union has instituted a special service similar to those for Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter,” JTA wrote. “This special service, started in 1925, showed a 30 percent increase in 1926.”

8. Rosh Hashanah was not always the Jewish New Year.

In the Torah , the beginning of the year was clearly set at the beginning of the month of Nisan, in the spring. However, sometime between the Torah and the codification of the Mishnah, Rosh Hashanah became the primary new year. The reasons are unclear, although some scholars theorize that it was because neighboring peoples in the ancient Near East celebrated their new years at this time.

9. The shofar, the traditional ram’s horn blown on Rosh Hashanah, is, well, stinky.

You have to get close to one to notice, but a common complaint is that these horns smell bad. According to online vendor The Shofar Man, all kosher shofar s have a bit of a scent because they come from a dead animal. To mitigate the odor, he suggests applying a sealant to the inside of the shofar. Believe it or not, several competing products are marketed exclusively for the purpose of removing or neutralizing shofar smells. We can’t vouch for any of them, but perhaps if they don’t work for your shofar, you could use them for your shoes, bathroom or car.

Happy New Year!